22 Dec 2025

Over the last decade, European democracies and beyond have faced a series of shocks, including the electoral rise of illiberal political parties and the COVID-19 pandemic. These developments may have reshaped how citizens relate to democratic institutions and institutional trust: the degree to which people rely on public institutions, feel represented by them, and see them as legitimate. A core objective of the INTERFACED project is to understand these dynamics, particularly among marginalised groups, while identifying both the sources of mistrust and potential pathways to reinforce trust in political institutions and in science.

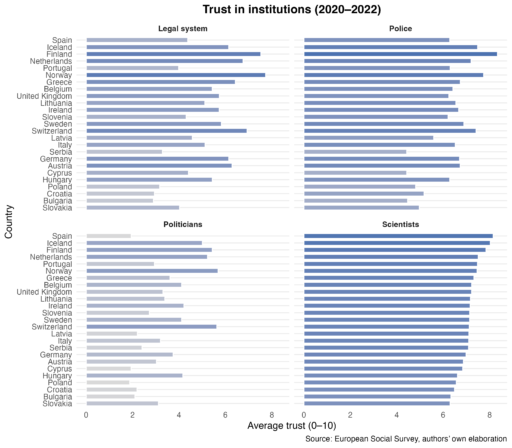

Against this backdrop, the figure below draws on data from the European Social Survey (ESS Round 10, 2020–2022) to compare average levels of trust (on a 0–10 scale) in four institutions across European countries: the legal system, the police, politicians, and scientists. The cross-national patterns are descriptive but striking. Trust in politicians is consistently low throughout Europe, even though there is meaningful variation between countries. By contrast, scientists are the most trusted actors across almost all contexts. Even in countries where confidence in political institutions is weak, trust in scientific expertise remains comparatively high. This hierarchy of trust is particularly visible in the wake of the pandemic, when scientific advice became central to public decision-making. At the same time, the increased prominence of science in public debates also meant that trust in experts was contested and, in some instances, politicised.

Within this broader comparison, Spain—one of the case studies in the INTERFACED project and a member of the consortium led by Carlos III University in Spain—presents an especially interesting picture. According to the ESS data, Spain ranks among the countries with the lowest levels of trust in politicians, while simultaneously showing the highest levels of trust in scientists. Now an established democracy, Spain celebrated this year the 50th anniversary of the start of its democratic transition in 1975. However, recent public opinion data have somewhat dampened this democratic milestone: 21% of the population expresses a positive view of the dictatorship. This trend is particularly troubling among young people, as one in every five individuals aged 18–24 has favourable views of the authoritarian past. Likewise, these youngest cohorts have been among the most affected by the social and political disruptions associated with COVID-19.

Taken together, these patterns raise important concerns for policy leaders and academia. They underline the importance of understanding how trust is distributed across institutions and how it connects to political engagement and democratic resilience. Understanding these dynamics is one of the challenges that the INTERFACED project is working to address.

Authors: Nerea Gándara Guerra, Universidad Carlos III of Madrid